The Films That Find Me When I Need Them Most

From Birdcage to Comet: On Grief, Memory. The Comfort Films I Return to Again and Again.

There are films that comfort like a cup of tea. Not because they’re gentle, but because they know how to sit with you in the dark.

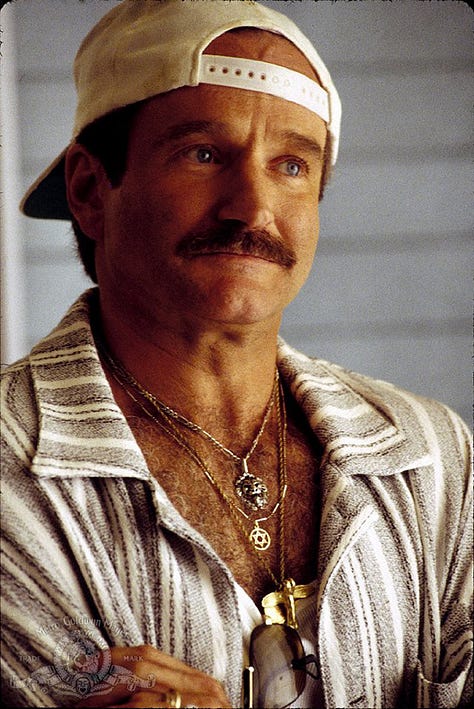

For me, The Birdcage, Mrs. Doubtfire, and the original Jumanji

form a kind of sacred trio. Each of them holds something larger than the script, the sets, or even the nostalgia they carry. They hold Robin Williams.

I loved him deeply—from afar. I still remember the day I learned he had died. I was in my room at my residence in Hamilton. The news struck like something personal. I remember sitting there, frozen. And then I did what I always do when I can’t process emotion—I wrote. A quiet, grieving tribute. I felt, irrationally but sincerely, that I had failed him. That if I had loved him harder, more visibly, maybe it would have made a difference. Some part of me still believes that.

The Birdcage—at first glance, it seems like a sweet, light comedy. But it’s much more than that. This film shines a bold, compassionate light on what it means to see someone’s soul before judging them through the lens of religious or gendered beliefs. Nathan Lane was subjected to so much mockery and hate from journalists after the film’s release—simply for having the time of his life playing the glorious, complicated character that he did. And Robin Williams defended him fiercely.

The performances still hold up today. This movie is just as funny in 2021 as it was in 1996—even if some aspects of the plot haven’t aged all that gracefully. But the moral? Timeless: Don’t lie about your fiancé’s family—or their fundamental identity—just to appease your parents. Especially if they’re incredible human beings.

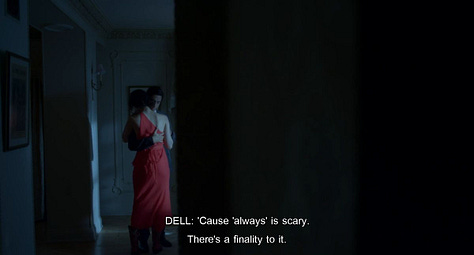

Then there’s Comet (2014)—a film that came into my life like a whispered secret and left me emotionally undone. Directed by Sam Esmail, it’s one of the most visually and emotionally striking films I’ve ever seen. It isn't for everyone, and that’s what makes it feel like it’s for me. The cinematography, lighting, and soundtrack are stunning, yes—but it’s the writing that took me apart. The characters aren’t just well-drawn, they feel lived-in. The dialogue is raw, elliptical, like real conversations you almost remember from dreams. Watching it felt like a transcendent experience, like slipping through time, or into a parallel version of myself. It reminded me of Mr. Nobody, another tv-show that left me quiet for days.

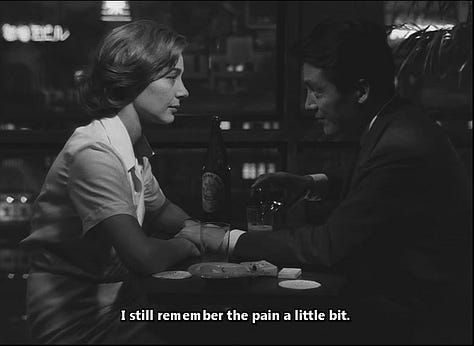

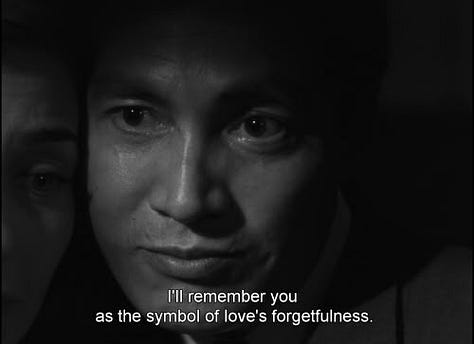

Some of these movies are beautiful in the way pain can be beautiful—Hiroshima Mon Amour is like that. It doesn’t explain itself. It just stirs. It lives in the creases of memory and longing. That film has a perfect response in me.

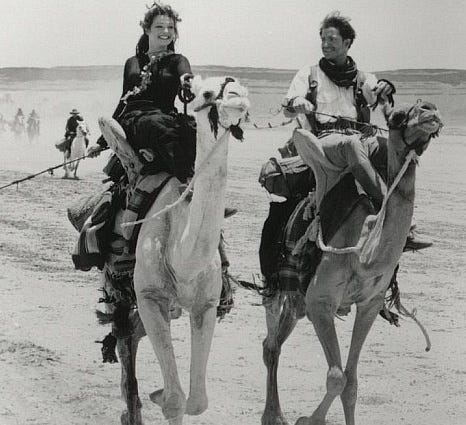

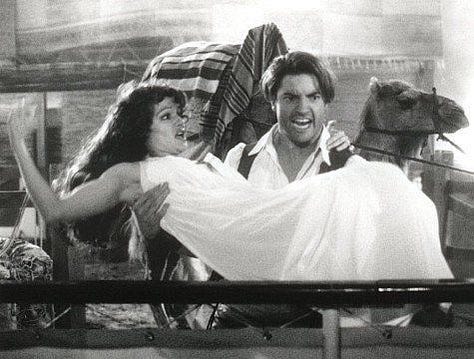

And then there’s The Mummy—but only the first part.

While everyone back then was bawling their eyes out over some painfully cheesy rom-coms like Dear John, The Notebook, or A Walk to Remember (I dislike everything about that kind of movie with all my heart), I was obsessed with The Mummy. I watched it every single day the summer after seventh grade. My mom even started questioning my mental health because I was legitimately pining over the fact that Rick wasn’t a real person.

But a love story wrapped up in horror? I mean—this isn’t really a horror film. It’s a classic monster movie, but the monstrous elements are totally played down in favour of the love triangle between Imhotep, Helen, and Rick (ugh, that man!).

There’s this one scene where Rick steals—well, “acquires”—tools for Evie so she can dig properly, simply because he admires her love for knowledge. Let me slow down here—GOD. MEN SUPPORTING WOMEN >

Dear god, I want to kiss those casting directors.

For all his general peak masculinity? Rick is feminist as hell. He’s just as dumbstruck by Evie as she is by him, and it’s so clear it’s not just a “whoa, she’s hot” moment. It’s deeper.

How do we know?

Because he steals her tools to dig with. That moment tells us he:

a) identified her passion for archaeology,

b) recognized her skill, even though the film never spells it out, and

c) wanted to make sure she could fully participate in the discovery of Hamunaptra.

P.S. there’s also a small, perfect moment when Evie gets a bit tipsy celebrating her architectural discovery—she’s giggly, overflowing with joy—and Rick just watches her. He doesn’t take advantage, doesn’t tease. He simply lets her be happy and makes sure she doesn’t trip over anything. He actually enjoys seeing her that way. Ugh. This.

And at no point does Rick try to take over. He knows his role—he’s the weapons expert, the muscle—and he’s completely fine with that. He follows Evie’s lead, always.

Another favorite moment: when they’re facing off with the American team on Day 1, and Evie realizes there’s a chamber beneath the Anubis statue. She gently places a hand on Rick’s arm, looks him in the eye, and says—very deliberately—“There are other places to dig.”

And he yields. Instantly. UGHHHHHHHHHH.

When I first saw the film, I was too young to realize how rare that dynamic was.

Meanwhile, Evie—with her adventurer’s heart trapped inside an academic world that keeps dismissing her because she’s a woman—is an absolute marvel. She’s coded visually as feminine: long hair, dresses, delicate frame. But that never undermines her competence or authority.

She’s consistently portrayed as a fully capable expert in Egyptology, and there’s not a single moment where she hesitates or loses control. Even when she falls into the “damsel in distress” role, it’s always a strategic decision—she weighs the risks, calculates the odds, and chooses to do what’s necessary for their survival.

Evie is never passive. She’s brash, brilliant, and constantly scheming. She even ends up saving the lives of the people who were supposed to rescue her. Please watch—and rewatch—this film. Let it remind you what real men look like, and that you are never just a damsel in distress.

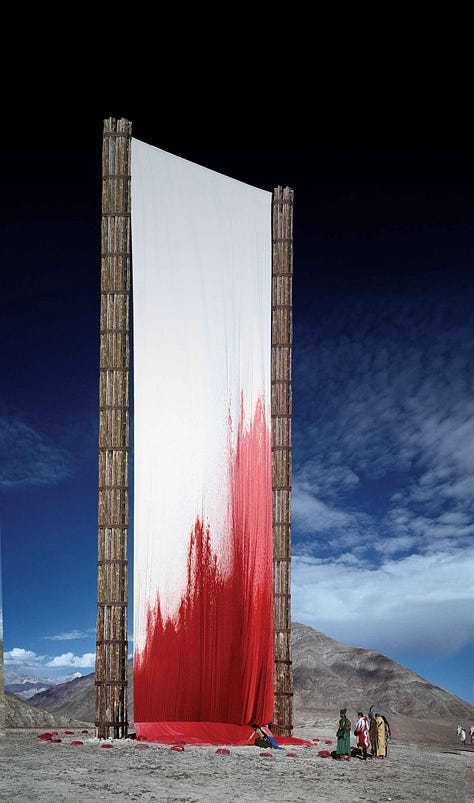

lastly, The Fall (2006). A visual love letter layered over a haunting story—Lee Pace, a hospitalized stuntman, spins a fantasy for a little girl, and the result is cinema magic. For someone like me—Slavic, sensitive, attuned to symbolism—The Fall stopped me in my tracks. The story unfolds in a hospital, where Roy (Lee Pace), injured and depressed, befriends Alexandria, a young girl. He weaves a fantastical tale of heroes battling evil, only for her imagination to reshape the narrative into something luminous, unpredictable, and deeply human.

Every frame of The Fall bursts with purpose. The cinematography is so visually stunning that you could pause at any moment and feel like you're looking at a painting in a museum. There are no CGI shortcuts—everything was filmed across more than 20 real-world locations, including Namibia, India, and Argentina, giving the movie an immersive, almost dreamlike quality. Colin Watkinson’s cinematography received widespread critical acclaim and is still considered one of his most beautiful bodies of work. And then there's Lee Pace—his performance is unforgettable: vulnerable, ornery, and quietly devastating. The emotional chemistry he shares with young Catinca Untaru carries the film, grounding its grand visual scale with raw, human tenderness.

Lee Pace has never looked more magnetic. If I'd seen him in this role as a teen, he may have shaped my aesthetic forever. The cinematography alone has earned its place among the most beautiful ever committed to film—deserving of frame-by-frame study.

Each of these films—The Birdcage, Mrs. Doubtfire, Jumanji, The Mummy, Comet, The Fall—holds a part of me. They’re not just nostalgic rewatches or emotional crutches; they’re memory markers. Anchors. They remind me who I was when I first saw them, and who I’ve become through each revisit. They’ve comforted me through grief, made me laugh in moments of loneliness, and showed me versions of love, courage, and identity I didn’t know how to name yet.

I return to them not because they’re perfect, but because they feel like home. And in a world that keeps moving, sometimes the most radical thing you can do is sit still with something that makes you feel safe—and whole.